Adolphe Monod and Antoine Vermeil

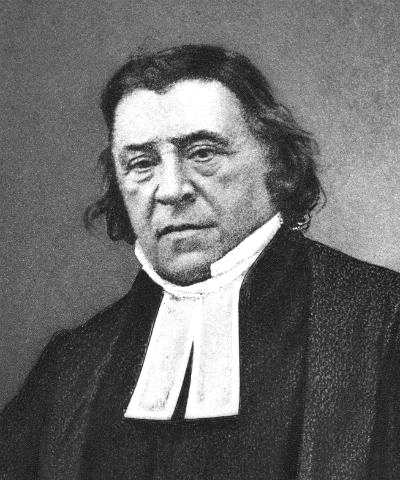

Antoine Vermeil (1799-1864)

In his monograph on the Deaconesses of Reuilly, Gustave Lagny (1912-2002) describes the youth of Antoine Vermeil and the first years of his ministry as follows:

“Antoine Vermeil was born in Nimes on the 19th of March 1799. His family was Huguenot and had its origins in Picardy. His mother came from the Rocheblave family and had been a fervent member of a Quaker group. His father was a merchant and tailor. Both had had their first communion in the “Désert”. They had only two children: Antoine and a younger son, Jules, who also became a pastor.

When he was young, Antoine was a good pupil. For some time he envisaged studying medicine, but he gave up this plan when he understood that he was called to directly serve Jesus Christ and his Church.

He studied theology in Geneva. He stayed there for seven years, first as a “student” and then as a “preacher”, from 1816 to 1823. These dates are important, because they marked the years of the Geneva awakening.

Antoine appears not to have been part of the small group of students of divinity who met with Robert Haldane. At that time he was new in Geneva and a very young student (18 years old). This notwithstanding, he was deeply influenced by the Awakening and all of his later ministry bore witness to it. His best friends, with whom he remained in friendly terms all of his life, had been directly influenced by this deep religious movement: their names were Frédéric and Guillaume Monod, Henri Merle d’Aubigné, Louis Vallette, Adolphe Monod. The subject of his thesis was “Religious Proselytism”. At that time he already had a deep concern for evangelism and the outreach of the Church, and this concern was his until the end of his life.

At the end of his studies, he was appointed to be an auxiliary pastor of the Church of Geneva. His gifts as a pulpit speaker were soon remarked. In April 1823 he preached on “the love of enemies” and deeply impressed his audience. The sermon led certain families of Geneva to reconcile with each other. As a consequence, Vermeil was offered the citizenship of Geneva.” (1)

Regardless of whether they were best friends or not, there is no doubt Adolphe Monod has known Vermeil in Geneva. In her biography of her father, Sarah Monod (1836-1912) mentions Vermeil:

“Adolphe Monod and his brother had completed the theology lessons and the mandatory exercises with other occupations. … As of their first student years, they and two fellow students, Mr Vermeil and Mr Lavil, established a small group “having as members all the candidates for the ministry who want to be admitted, and having the purpose of providing some literary exercises and exercises of composition that are not offered in the lectures, or which are very insufficient and which each student only performs very rarely, because of the great number of students. We think that among the twenty students of our class, about ten could become members of our group; the others are too busy or belong to the opposition.” … Their meetings were dedicated to reading, composing, improvisation and recitation exercises.” (2)

Vermeil leaves Geneva in 1823 in order to be the pastor of the French church of Hamburg (Germany), succeeding to Jean-Henri Merle d’Aubigné (1794-1872). He then receives a call to Bordeaux in 1824 (3).

Having left Geneva, too, Adolphe stays in contact with Vermeil. In a letter dated February 14, 1825, he writes to pastor Bouvier:

“… They say that Vermeil is generally appreciated in Bordeaux and that the people there love him. I am not astonished to the least. I wait for a letter on his behalf …” (4)

As a matter of fact, according to Gustave Lagny, the work he accomplishes in Bordeaux is impressive:

“… Vermeil’s time in Bordeaux is distinguished by a series of undertakings aimed at equipping the parish with bodies for a great variety of tasks. In 1829 he created a “Bureau for protestant charity”. In order to make it operational, he created a “Charitable society” comprising 36 ladies in the same year. Being spread over the different town districts, their task was to provide some sort of home-based social assistance. About at the same time, in 1830, he established a “Sunday school” and organised an advanced catechism for adults, both of which were quite a success. A little later he supported the establishment of a protestant elementary school (“Ecole des Chartrons”) and an infant school (1832). And then he was the driving force behind the construction of a second church in Bordeaux (“Temple des Chartrons”) and the establishment of a protestant cemetery.

Moreover, he looked well beyond his parish and considered the French protestant Churches as a whole. Thus Vermeil himself proposed, requested and undertook a great variety of efforts in order to provide for “general needs”. As of 1829, he created an “Organisation for the Welfare of Widows and Orphans of Pastors”. In 1834, together with two other pastors, he laid the foundations for the “Christian Protestant Society of France” the purpose of which was to help and associate the Protestant diaspora and to extend the influence of evangelical protestantism by all means (publications, sermons, …), anticipating what would be the programme of the “Central Society for Evangelisation” (a heiress of the “Christian Society of Bordeaux and several other societies of that kind) thirteen years later. He was interested in the training of pastors, in theological faculties and he was part of the council for the selection of professors for the theological faculty in Montauban. Together with a musician, professor Rimmer, he worked on the revision of the old Psalter (1833-1836). … Finally, in view of the authority conferred by his local ministry and the place he held, at the age of 35, in the Reformed churches of France, he was chosen to be part of the “Task force” established by François Guizot in 1834.” (5)

In 1826 Vermeil marries Louise Paschoud, the daughter of a librarian and editor of Geneva. They have at least one son, Antoine Henri Vermeil, born in 1842.

We are not in possession of letters between Adolphe Monod and Antoine Vermeil after 1825, but the (liberal) colleague of Adolphe Monod in Lyon, Joseph Martin-Paschoud (1802-1873) is the husband of one of Mrs Vermeil’s sisters. It is likely that there have been contacts at least via this connection in the 1830s.

Vermeil receives several calls to be a pastor in Paris. For instance, he is asked tor replace Jean Monod after his death in 1836. Vermeil declines the offer. (6)

After a few years tainted by conflicts, however, Vermeil leaves Bordeaux in 1840 and becomes a pastor in Paris. It is at that time that the project of a community of deaconesses becomes a reality. Monod is one of the professors of the faculty of Montauban. One of his sermons, given in Bordeaux, convinces Caroline Malvesin, the future head of the Decaonesses of Reuilly, of her calling (7) (see my note on “Adolphe Monod and Caroline Malvesin”). The community comes into existence in 1841. Incidentally, the vice-president of the Board of directors as of 1842 is Louis Vallette (8), also a former fellow student and friend of Adolphe Monod (see my note on “Adolphe Monod and Louis Vallette”).

Antoine Vermeil and Adolphe Monod both participate in the conference that takes place in London in 1846 and in which the Universal Evangelical Alliance is established. (9)

The first years of the community of deaconesses are overshadowed by attacks both from the liberal branch (led by Athanase Coquerel (1820-1875)) and from some representatives of the evangelical branch (above all Valérie de Gasparin (1813-1894)) of the national Church. Adolphe Monod becomes pastor in Paris in the midst of these troubled times, in 1847. He appears not to have voiced his support to the deaconesses, but to have encouraged their leaders. At least this is what Gustave Lagny suggests:

“Many in our Churches perceived what was specious and unjust in the critique of Mrs de Gasparin and Athanase Coquerel. Even when they did not directly support the cause of a community of deaconesses, they expressed their friendship to our Community or to its leaders, and the warmth of those expressions was as great as was their grief to see how much both were misunderstood. Among those supporters we will cite only a few great names: Adolphe Monod, Henri Grandpierre, Jules Pédezert …” (10)

In the year 1851 the government tries to reorganise the Reformed Church. The minister in charge of public education and religious communities, the Baron de Crouseilhes (1792-1862), envisages summoning a national synod. Within this context, the establishment of a seven-member commission was foreseen; Vermeil and Monod were to be part of it (11).

We also find the two men cited in the answer (dated May 16, 1853) of the prefect of the Gironde region, Georges Haussmann (1809-1891), to the letter of the minister in charge of public education Hippolyte Fortoul (1811-1856), who had asked the prefects who they “thought to be the most respected, authorised and wise persons among the protestants of [their] department”. Haussmann, who is hostile to the liberals, criticises the composition of the central Council and suggests that Monod and Vermeil be consulted more often (12).

When Adolphe Monod is dying in 1856, Vermeil is among those who accompany him. The book Les adieux cites the names of the pastors presiding the religious offices that were organised around the dying pastor: “Mr Frédéric Monod, Guillaume Monod, Meyer, Grandpierre, Gauthey, Vaurigaud (of Nantes), Vallette, Armand-Delille, Vermeil, Fisch, Jean Monod, Edmond de Pressensé, Petit, Paumier, Zipperlen, Hocart, Louis Vernes, Boissonnas and Vulliet.” (13)

At that time, Vermeil still presides the Community of the deaconesses. There are no more vigorous attacks against the community, but Vermeil is exhausted. “I feel that my forces betray my will”, he says (14). As a matter of fact, Louis Vallette de facto is president as of 1857, and he continues the work after Vermeil’s death, on October 18, 1864.

Sources:

- Sarah Monod, Adolphe Monod, I. Souvenirs de sa vie. Extraits de sa correspondance, Paris, Librairie Fischbacher, 1885, 479 p. A partial English translation is available : Life and letters of Adolphe Monod, pastor of the Reformed Church of France, London, J. Nisbet & Co., 1885, 426 p.

- Les adieux d’Adolphe Monod à ses amis et à l’Eglise, Meyrueis, Paris, 1856, 191 p. An English translation is available: Adolphe Monod’s Farewell to His Friends and to the Church, R. Carter & Brothers, 1858, 183 p.

- Gustave Lagny, Le réveil de 1830 à Paris et les origines des diaconesses de Reuilly, Paris, Association des diaconesses, 1958, 195 p. (re-published in 2007 by Editions Olivetan)

- André Encrevé, Protestants français au milieu du XIXe siècle, Genève, Labor et Fides, 1986, 1121 p.

Footnotes

(1) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 37s. (our emphasis)

(2) Sarah Monod, Souvenirs, p. 14. (our emphasis)

(3) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 38

(4) Sarah Monod, Souvenirs, p. 69

(5) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 40s

(6) Allgemeine Kirchenzeitung of July 11, 1840

(7) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 49s

(8) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 74

(9) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 135

(10) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 129 ; cf. p. 180

(11) Encrévé, Protestants …, p. 226

(12) Encrévé, Protestants …, p. 556

(13) Les adieux, p. III (our emphasis)

(14) Gustave Lagny, Le Réveil …, p. 151

Download as a .pdf file

back to the Adolphe Monod primer |

|

|